Recommended Reading Vol. I and Vol. II

We are often asked for a list of recommended books on Indian Boarding School history and experiences in the U.S. Knowing our history and speaking the truth are just the beginning of the ways in which we can bring about healing and transformation for ourselves, our families and communities, and our Nations here on Turtle Island. We are happy to share this sampling of books and we encourage you to share and read with others.

Volume I

|

Drawing from hundreds of letters by students, parents, and school officials, Boarding School Seasons examines student experiences at three institutions between 1900 and 1940. Written by Dr. Brenda Child, a Red Lake Ojibwe woman and a descendant of boarding school survivors, this book primarily focuses on Haskell Institute (Kansas), Flandreau (South Dakota), and Pipestone (Minnesota). Dr. Child, who is a Professor of American Studies at the University of Minnesota, earned the 1995 North American Indian Prose Award for Boarding School Seasons. |

|

Telling this history in the voice of when he was a student there, Adam Fortunate Eagle shares his experience at Pipestone Indian Boarding School in Minnesota between 1935 and 1945. This first-hand account offers unique insights regarding the diverse array of experiences that were seen in the Indian boarding school era. Pipestone: My Life in an Indian Boarding School delivers a narrative not often explored given positive personal anecdotes, student pranks, and the reminiscing of dormitory culture. Adam Fortunate Eagle (Red Lake Ojibwe) is perhaps best known as the principal organizer for the Occupation of Alcatraz between 1969 and 1971. |

|

First published in 1900, The Middle Five is an autobiographical account of the Francis LaFlesche’s experience as a student in a Presbyterian boarding school in northeastern Nebraska. The personal stories of La Flesche (Omaha) are told in the voice of the students and shine light on what life was like for them. The book is a unique perspective, as La Flesche’s purpose of the text, in his own words, was “to present the companions of my own young days to the children of the race that has become possessed of the land of my fathers.” |

|

Authored by education professor and former NABS board member, Dr. Denise K. Lajimodiere, this book explores the enduring impacts of the boarding school era in the Dakota's and Minnesota and the relationship they hold to historical and intergenerational trauma. Dr. Lajimodiere's research is an extension of her interest in the stories of her father and other family members who were subjected to and survived the federal governments' assimilation policy that compelled the proliferation of the boarding school model. The insights gained through her research invited Dr. Lajimodiere to more profoundly understand the way in which she and her siblings were raised, as well as other family members of whom were so closely impacted by the boarding school era. The book features sixteen interviews with boarding school survivors and is culminated by the author's own healing process with her father. |

| They Called Me Uncivilized: The Memoir of an Everyday Lakota Man from Wounded Knee Born in 1942 in Wounded Knee on the Pine Ridge reservation in South Dakota, Walter Littlemoon’s (Lakota) memoir, They Called Me Uncivilized, describes the impact that federal Indian policies had on his life and on the history of his family. This narrative offers a rare glimpse inside the cruelty of the U.S. government boarding school policy on to generations of Native American children. They Called Me Uncivilized also provides a unique view of the 1973 militant Occupation of Wounded Knee and the lasting impact that the takeover had on the community. |

| A Voice in Her Tribe: A Navajo Woman’s Own Story (D. O. Dawdy, Ed.) Irene Stewart’s (Dine/Navajo), A Voice in Her Tribe, is a powerful memoir that recounts her life from birth through childhood and beyond, including her time as an industrial school student. Her compelling testimony reflecting her industrial education experience characterizes the callous treatment first-hand. Stewart’s writing explores the unique challenges of biculturality as a Navajo woman in a changing world where imposed settler values and new systems of power and culture posed a great challenge to existing between two worlds. |

| Boarding School Blues: Revisiting American Indian Educational Experiences The boarding school experience became part of Native American history, with some students using this experience to expand their own knowledge and help their people. This volume of essays edited and introduced by Dr. Clifford Trafzer, Dr. Jean Keller, and Lorene Sisquoc (Fort Sill Apache/Cahuilla) documents a vast array of Native American boarding school experiences, both positive and negative. With a great range of voice, Boarding School Blues does well in addressing issues such as runaways, sports, punishment, Christianity, and the physical plants themselves.

|

|

Dr. Alfred Taiaiake (Kanienkehaka /Mohawk) puts forth a profound vision for the Indigenous Peoples of North America in this important manifesto. In Peace, Power, and Righteousness, Alfred invites Indigenous People to move beyond the 500-year history of pain, loss, and colonization, and move toward an engaged and liberatory form of self-determination. With an intimate knowledge and sensibility of the trauma of colonization, this volume calls for a way forward that is conscious of and honors traditional ways to educate a new generation of Indigenous leaders. |

|

Look to the Mountain is an invaluable resource for educators looking to ground their practice in Indigenous ways of knowing and being. Dr. Gregory Cajete is a Tewa Indian from Santa Clara Pueblo, New Mexico, and expertly draws profound distinctions between Indigenous ways of teaching and thinking and ones frequently seen in contemporary American education. This book deeply reconceptualizes what can be accomplished under the banner of Indigenous education, featuring a commitment to the foundations of the spiritual, environmental, mythic, visionary, artistic, affective, and the communal. Overall, Dr. Cajete shows that Indigenous education is a process of education that is grounded in the foundations of human nature. |

| Power and Place: Indian Education in America In this volume of essays, Dr. Vine Deloria Jr. (Standing Rock Sioux) and Dr. Daniel R. Wildcat (Yuchee Creek) examine various issues facing Native American students in their experience in schools, colleges, and later into professional life. The visionary nature of Power and Place engages both philosophical and practical lessons for administrators, educators, students and community leaders in Indian Education. Deloria Jr. and Wildcat effectively reveal those unique nuances that Indigenous approaches to learning, knowing, and being can address the contradictions made apparent within contemporary American education. |

| Healing the Soul Wound: Trauma-informed Counseling for Indigenous Communities As a clinical psychologist who has worked in Indian country for several decades, Dr. Eduardo Duran—who was born in New Mexico and also previously worked as a migrant farmworker—offers a uniquely subversive method of healing and counseling that is grounded in Indigenous ways of being. Healing the Soul Wound centers its focus on the legacy of historical trauma and explores theoretical Indigenous understanding of cosmology and how understanding natural law can lead to new ways of understanding and healing the psyche. This book offers a culture-specific approach that is often ignored in modern healing work. |

|

Braiding Sweetgrass poetically bridges modern theories of biology and ecology with ancestral wisdom and Indigenous consciousness. Dr. Robin Wall Kimmerer (Potawatomi) eloquently shows that by combining the knowledge of modern science and the traditional Indigenous understandings, we can more deeply engage in a world that is seeking to connect with us as a teacher and a relative. Reflecting that truth Kimmerer states, “Because the relationship between self and the world is reciprocal, it is not a question of first getting enlightened or saved and then acting. As we work to heal the earth, the earth heals us.” |

| All Our Relations: Native Struggles for Land and Life Charting the struggle of Native resistance against environmental and cultural degradation, Winona LaDuke (White Earth Ojibwe) offers an inspiring call toward self-determination and community through historical analysis, testimonies, and reflections. All Our Relations features chapters on the Seminoles, the Anishinaabeg, the Innu, the Northern Cheyene, and the Mohawk Nations, among others. |

|

One of the first books of its kind, Decolonizing Trauma Work, is an invaluable resource for those that work in healthcare, education, healing, clinical services, and policy writing, especially when it comes to healing and wellness in Indigenous communities. Dr. Renee Linklater (Rainy River First Nations) presents practical methods that are designed to support individuals and communities that have experienced trauma through an Indigenous worldview, embedded with cultural knowledge. |

|

As is so often seen in culture, education, and politics, American history tends to neglect the stories of Native America past the Wounded Knee Massacre of 1890. Dr. David Treuer (Leech Lake Ojibwe) seeks to counter that narrative with The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee, a volume that combines history with memoir, exploring the evolving structures of colonial structures of legal and political maneuvers that resulted in further land seizures in the 20th century, as well as how Indian boarding schools were a crucial part of that strategy. This book is a powerful accounting of an era that has been noticeably missing from common historical accounts of the U.S. |

| American Indian Education 2nd edition Before Europeans arrived in North America, Indigenous peoples spoke more than three hundred languages and followed almost as many distinct belief systems and lifeways. But in childrearing, the different Indian societies had certain practices in common—including training for survival and teaching tribal traditions. The history of American Indian education from colonial times to the present is a story of how Euro-Americans disrupted and suppressed these common cultural practices, and how Indians actively pursued and preserved them. American Indian Education recounts that history from the earliest missionary and government attempts to Christianize and “civilize” Indian children to the most recent efforts to revitalize Native cultures and return control of schools to Indigenous peoples. Extensive firsthand testimony from teachers and students offers unique insight into the varying experiences of Indian education. Historians and educators Jon Reyhner and Jeanne Eder begin by discussing Indian childrearing practices and the work of colonial missionaries in New France (Canada), New England, Mexico, and California, then conduct readers through the full array of government programs aimed at educating Indian children. From the passage of the Civilization Act of 1819 to the formation of the Bureau of Indian Affairs in 1824 and the establishment of Indian reservations and vocation-oriented boarding schools, the authors frame Native education through federal policy eras: treaties, removal, assimilation, reorganization, termination, and self-determination. Thoroughly updated for this second edition, American Indian Education is the most comprehensive single-volume account, useful for students, educators, historians, activists, and public servants interested in the history and efficacy of educational reforms past and present. |

|

An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States for Young People is a fully adapted text by renowned curriculum experts Debbie Reese (Nambé Pueblo) and Jean Mendoza. This text takes a similar shape to the original academic text by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz in content and theme, though re-framed to engage a younger audience. Designed primarily with middle-grade and young adult readers in mind, the book includes discussion topics, archival images, original maps, recommendations for further reading, and other materials to encourage students, teachers, and general readers to think critically about their own place in history. |

|

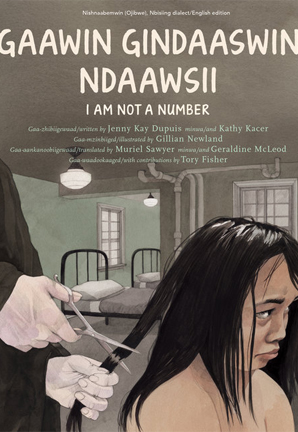

When eight-year-old Irene is removed from her First Nations family to live in a residential school she tries to remember who she is and where she came from, despite the efforts of the nuns who are in charge at the school and who tell her that she is not to use her own name but instead use the number they have assigned to her. Irene's parents decide never to send her and her brothers away again. But where will they hide? And what will happen when her parents disobey the law? Based on the life of co-author Jenny Kay Dupuis’ (Ojibwe) grandmother, I Am Not a Number is a hugely necessary book that brings a terrible part of Canada’s history to light in a way that children can learn from and relate to. There are two versions of this book, one in English, and one in a dual-language version in Nishnaabemwin (Ojibwe) Nbisiing dialect and English. |

|

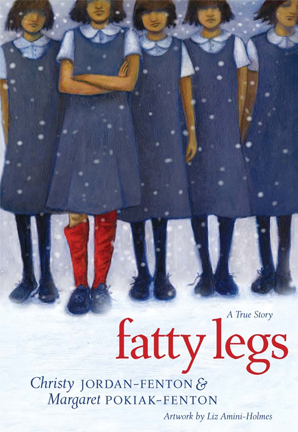

Eight-year-old Margaret Pokiak has set her sights on learning to read, even though it means leaving her village in the high Arctic. Her father finally agrees but he warns Margaret of the terrors of residential schools. At school, Margaret soon encounters the Raven, a black-cloaked nun with a hooked nose and bony fingers that resemble claws. Intending to humiliate her, the heartless Raven gives gray stockings to all the girls — all except Margaret, who gets red ones. In the end, it is this brave young girl who gives the Raven a lesson in the power of human dignity. Written by Margaret Pokiak-Fenton (Inuit) and her daughter-in-law Christy Jordan-Fenton, Fatty Legs is complemented by archival photos from Pokiak-Fenton’s collection and striking art from Liz Amini-Holmes, this inspiring first-person account of a girl’s determination to confront her tormentor will linger with young readers in middle grades. |

|

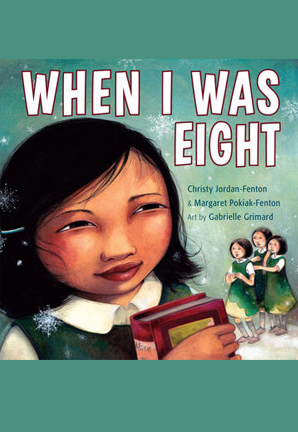

For Inuit children in boarding schools, the cost of learning to read English is a high one. Cutting their hair and taking their traditional clothing and name away is just the start of the systematic removal of identity and culture. When I Was Eight is a visceral telling of Margaret Pokiak-Fenton’s childhood in the form of a beautifully written and honest picture book that will reverberate with readers. This adaptation of Fatty Legs for younger grade readers evokes the same themes in a re-designed manner appropriate for early readers. |

|

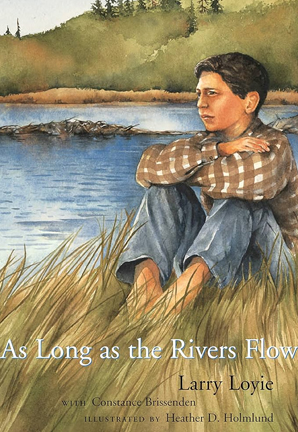

In an attempt to erase language and culture from First Nation’s children, they were forcibly removed from their homes and sent away to government-sponsored church-run boarding schools. As Long as the River Flows shares the story of Larry Loyie's (Cree) last summer before entering residential school and all he learned and experienced before life changed forever. |

|

Drama and humor combine in Goodbye Buffalo Bay by award-winning Cree author Larry Loyie. The sequel to As Long as the Rivers Flow, this book is set during the author's teenage years. In his last year in residential school, Lawrence learns the power of friendship and finds the courage to stand up for his beliefs. He returns home to find the traditional First Nations life he loved has changed dramatically. He feels like a stranger to his family until his grandfather's gentle guidance helps him find his way. Goodbye Buffalo Bay explores the themes of self-discovery, the importance of friendship, the difference between anger and assertiveness and the realization of youthful dreams. |

|

In the 1930s two young brothers are sent to a government-run Indian residential school — an experience shared by generations of Native American children. At these schools, children are forbidden to speak their native tongue and are taught to abandon their Indian ways. In this multi-award-winning book, Native American artist Judith Lowry’s illustrations are inspired by the stories she heard from her father and uncle. The lyrical narrative and compelling paintings blend memory and myth in this bittersweet story of the boys’ journey home one summer and the healing power of their culture. |

|

Her name was Seepeetza when she was at home with her family. But now that she's living at the Indian residential school her name is Martha Stone, and everything else about her life has changed as well. Told in the honest voice of a sixth-grader, this is the story of a young Native girl forced to live in a world governed by strict nuns, arbitrary rules, and a policy against talking in her own dialect, even with her family. Seepeetza finds bright spots, but most of all she looks forward to summers and holidays at home. |

|

This collection, in prose memoir and poetry, describes attending a government school for Indian children and the challenges presented socially, culturally, and expressively. Dr. Laura Tohe (Diné) was born in Fort Defiance, Arizona, and grew up on the Navajo Reservation in Arizona and New Mexico. When they moved to Crystal, New Mexico, Tohe’s mother worked at a boarding school close by. This book originates from a story given to her mother by her great-grandmother. Dr. Tohe—who is also a Navajo Nation Poet Laureate (2015-2019) is a professor emerita of English at Arizona State University. |

|

Inspired by true events, this story of strength, family, and culture shares the awe-inspiring resilience of Elder Betty Ross. Abandoned as a young child, Betsy is adopted into a loving family. A few short years later, at the age of 8, everything changes. Betsy is taken away to a residential school. There she is forced to endure abuse and indignity, but Betsy recalls the words her father spoke to her at Sugar Falls―words that give her the resilience, strength, and determination to survive. Sugar Falls is based on the true story of Betty Ross, Elder from Cross Lake First Nation. We wish to acknowledge, with the utmost gratitude, Betty’s generosity in sharing her story. A portion of the proceeds from the sale of Sugar Falls goes to support the bursary program for The Helen Betty Osborne Memorial Foundation. This 10th-anniversary edition brings David A. Robertson’s national bestseller to life in full color, with a foreword by The Hon. Murray Sinclair, Chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, and a touching afterword from Elder Betty Ross herself. |

|

Taken from their families when they are very small and sent to a remote, church-run residential school, Kenny, Lucy, Clara, Howie and Maisie are barely out of childhood when they are finally released after years of detention. Alone and without any skills, support or families, the teens find their way to the seedy and foreign world of Downtown Eastside Vancouver, where they cling together, striving to find a place of safety and belonging in a world that doesn’t want them. The paths of the five friends cross and crisscross over the decades as they struggle to overcome, or at least forget, the trauma they endured during their years at the Mission. Fuelled by rage and furious with God, Clara finds her way into the dangerous, highly charged world of the American Indian Movement. Maisie internalizes her pain and continually places herself in dangerous situations. Famous for his daring escapes from the school, Kenny can’t stop running and moves restlessly from job to job—through fishing grounds, orchards and logging camps—trying to outrun his memories and his addiction. Lucy finds peace in motherhood and nurtures a secret compulsive disorder as she waits for Kenny to return to the life they once hoped to share together. After almost beating one of his tormentors to death, Howie serves time in prison, then tries once again to re-enter society and begin life anew. With compassion and insight, Five Little Indians chronicles the desperate quest of these residential school survivors to come to terms with their past and, ultimately, find a way forward. |

|

(For grades 1st and up) The story of the beautiful relationship between a little girl and her grandfather. When she asks her grandfather how to say something in his language – Cree – he admits that his language was stolen from him when he was a boy. The little girl then sets out to help her grandfather find his language again. This sensitive and warmly illustrated picture book explores the intergenerational impact of the residential school system that separated young Indigenous children from their families. The story recognizes the pain of those whose culture and language were taken from them, how that pain is passed down, and how healing can also be shared. |

Volume II

|

Education beyond the Mesas is the fascinating story of how generations of Hopi schoolchildren from northeastern Arizona “turned the power” by using compulsory federal education to affirm their way of life and better their community. Sherman Institute in Riverside, California, one of the largest off-reservation boarding schools in the United States, followed other federally funded boarding schools of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in promoting the assimilation of indigenous people into mainstream America. Many Hopi schoolchildren, deeply conversant in Hopi values and traditional education before being sent to Sherman Institute, resisted this program of acculturation. Immersed in learning about another world, generations of Hopi children drew on their culture to skillfully navigate a system designed to change them irrevocably. In fact, not only did the Hopi children strengthen their commitment to their families and communities while away in the “land of oranges,” they used their new skills, fluency in English, and knowledge of politics and economics to help their people when they eventually returned home. Matthew Sakiestewa Gilbert draws on interviews, archival records, and his own experiences growing up in the Hopi community to offer a powerful account of a quiet, enduring triumph. |

|

Bloomfield Academy was founded in 1852 by the Chickasaw Nation in conjunction with missionaries. It remained open for nearly a century, offering Chickasaw girls one of the finest educations in the West. After being forcibly relocated to Indian Territory, the Chickasaws viewed education as instrumental to their survival in a rapidly changing world. Bloomfield became their way to prepare emerging generations of Chickasaw girls for new challenges and opportunities. Amanda J. Cobb became interested in Bloomfield Academy because of her grandmother, Ida Mae Pratt Cobb, an alumna from the 1920s. Drawing on letters, reports, interviews with students, and school programs, Cobb recounts the academy’s success story. In stark contrast to the federally run off-reservation boarding schools in operation at the time, Bloomfield represents a rare instance of tribal control in education. For the Chickasaw Nation, Bloomfield—a tool of assimilation—became an important method of self-preservation. |

|

This is the story of the Hopi woman who chose in her early youth to live in the white man's world. She became known as Elizabeth Q. White. Born at Old Oraibi, Arizona, she was of the first Hopi children to be educated in white schools. Later she was the first Hopi to become a teacher in those schools. Here her biographer records Qoyowayma's break with the traditions of her people and her struggle to gain acceptance for her radical teaching methods. Throughout her life this remarkable woman has held to the best in Hopi culture and has fought to maintain it in the lives of her students. Her story, rich in information on Hopi legend and ceremony, is a moving introduction to the Hopi way of life. |

|

The most enduring feature of U.S. history is the presence of Native Americans, yet most histories focus on Europeans and their descendants. This long practice of ignoring Indigenous history is changing, however, as a new generation of scholars insists that any full American history address the struggle, survival, and resurgence of American Indian nations. Indigenous history is essential to understanding the evolution of modern America. Ned Blackhawk interweaves five centuries of Native and non‑Native histories, from Spanish colonial exploration to the rise of Native American self-determination in the late twentieth century. In this transformative synthesis he shows that European colonization in the 1600s was never a predetermined success; Native nations helped shape England’s crisis of empire;

Blackhawk’s retelling of U.S. history acknowledges the enduring power, agency, and survival of Indigenous peoples, yielding a truer account of the United States and revealing anew the varied meanings of America. |

|

Injustice has plagued American society for centuries. And we cannot move toward being a more just nation without understanding the root causes that have shaped our culture and institutions. In this prophetic blend of history, theology, and cultural commentary, Mark Charles and Soong-Chan Rah reveal the far-reaching, damaging effects of the "Doctrine of Discovery." In the fifteenth century, official church edicts gave Christian explorers the right to claim territories they "discovered." This was institutionalized as an implicit national framework that justifies American triumphalism, white supremacy, and ongoing injustices. The result is that the dominant culture idealizes a history of discovery, opportunity, expansion, and equality, while minority communities have been traumatized by colonization, slavery, segregation, and dehumanization. Healing begins when deeply entrenched beliefs are unsettled. Charles and Rah aim to recover a common memory and shared understanding of where we have been and where we are going. As other nations have instituted truth and reconciliation commissions, so do the authors call our nation and churches to a truth-telling that will expose past injustices and open the door to conciliation and true community. |

|

Eaglespeaker, Jason. 2014 The chilling chronicles of a family's exploitation in Canada's notorious residential schools. It began as a single scrapbook, created for educators. UNeducation, Vol 1 is now in schools, universities, libraries, treatment/corrections centers, healing initiatives, government agencies and educator trainings worldwide. Gain a full and proper education about a dark episode in North American history. These haunting chapters await:

|

|

From the mid-century metropolis of Chicago to the windswept ancestral lands of the Dakota people, to the bleak and brutal Indian boarding schools, A Council of Dolls is the story of three women, told in part through the stories of the dolls they carried.... Sissy, born 1961: Sissy's relationship with her beautiful and volatile mother is difficult, even dangerous, but her life is also filled with beautiful things, including a new Christmas present, a doll called Ethel. Ethel whispers advice and kindness in Sissy's ear, and in one especially terrifying moment, maybe even saves Sissy's life. Lillian, born 1925: Born in her ancestral lands in a time of terrible change, Lillian clings to her sister, Blanche, and her doll, Mae. When the sisters are forced to attend an "Indian school" far from their home, Blanche refuses to be cowed by the school's abusive nuns. But when tragedy strikes the sisters, the doll Mae finds her way to defend the girls. Cora, born 1888: Though she was born into the brutal legacy of the "Indian Wars," Cora isn't afraid of the white men who remove her to a school across the country to be "civilized." When teachers burn her beloved buckskin and beaded doll Winona, Cora discovers that the spirit of Winona may not be entirely lost. |

| Stealing, A Novel A gripping, gut-punch of a novel about a Cherokee child removed from her family and sent to a Christian boarding school in the 1950s—an ambitious, eye-opening reckoning of history and small-town prejudices from Pulitzer Prize finalist Margaret Verble. Kit Crockett lives on a farm with her grief-stricken, widowed father, tending the garden, fishing in a local stream, and reading Nancy Drew mysteries from the library bookmobile. One day, Kit discovers a mysterious and beautiful woman has moved in just down the road. Kit and the newcomer, Bella, become friends, and the lonely Kit draws comfort from her. But when a malicious neighbor finds out, Kit suddenly finds herself at the center of a tragic, fatal crime and becomes a ward of the court. Her Cherokee family wants to raise her, but the righteous Christians in town instead send her to a religious boarding school. Kit’s heritage is attacked, and she’s subjected to religious indoctrination and other forms of abuse. But Kit secretly keeps a journal recounting what she remembers—and revealing just what she has forgotten. Over the course of Stealing, she unravels the truth of how she ended up at the school and plots a way out. If only she can make her plan work in time. |

|

When wellness teachers and husband-wife duo Chelsey Luger and Thosh Collins founded their Indigenous wellness initiative, Well for Culture, they extended an invitation to all to honor their whole self through Native wellness philosophies and practices. In reclaiming this ancient wisdom for health and wellbeing—drawing from traditions spanning multiple tribes—they developed the Seven Circles, a holistic model for modern living rooted in timeless teachings from their ancestors. Luger and Collins have introduced this universally adaptable template for living well to Ivy league universities and corporations like Nike, Adidas, and Google, and now make it available to everyone in this wise guide. |

|

Discover the profound wisdom of the Anishinaabeg/Ojibwe people in "The Seven Generations and The Seven Grandfather Teachings." In this captivating journey, you will immerse yourself in timeless teachings that illuminate the way to interconnectedness and interdependence. As the spiritual translation of the sacred laws, the Seven Grandfather teachings guide us towards Mino-bimaadiziwin, "the good life" – a life of harmony, free from contradiction or conflict. Prepare to embark on a transformative path of peace and balance, where ancestral knowledge offers invaluable lessons for a fulfilling existence. |

|

Winner of the Gourmand International World Cookbook Award,Recovering Our Ancestors’ Gardens is back! Featuring an expanded array of tempting recipes of indigenous ingredients and practical advice about health, fitness, and becoming involved in the burgeoning indigenous food sovereignty movement, the acclaimed Choctaw author and scholar Devon A. Mihesuah draws on the rich indigenous heritages of this continent to offer a helpful guide to a healthier life. |

|

Author Leigh Joseph, an ethnobotanist and a member of the Squamish Nation, provides a beautifully illustrated essential introduction to Indigenous plant knowledge. Plants can be a great source of healing as well as nourishment, and the practice of growing and harvesting from trees, flowering herbs, and other plants is a powerful way to become more connected to the land. The Indigenous Peoples of North America have long traditions of using native plants as medicine as well as for food. |

|

Robert Hentry et al. 2018 Indigenous peoples globally have a keen understanding of their health and wellness through traditional knowledge systems. In the past, traditional understandings of health often intersected with individual, community, and environmental relationships of well-being, creating an equilibrium of living well. However, colonization and the imposition of colonial policies regarding health, justice, and the environment have dramatically impacted Indigenous peoples’ health. |

|

Set in the Vancouver area in the late 1940s and through to the present day, this candid account follows Sam from his idyllic childhood growing up on the Eslhá7an (Mission) reserve to the confines of St. Paul’s Indian Residential School and then into a life of addiction and incarceration. But an ember of Sam’s spirit always burned within him, and even in the darkest of places he retained his humor and dignity until he found the strength to face his past. The Fire Still Burns is an unflinching look at the horrors of a childhood spent trapped within the Indian Residential School system and the long-term effects on survivors. It illustrates the healing power of one’s culture and the resilience that allows an individual to rebuild a life and a future. |

|

Originally published in 2010, Broken Circle: The Dark Legacy of Indian Residential Schools chronicles the impact of Theodore Fontaine’s harrowing experiences at Fort Alexander and Assiniboia Indian Residential Schools, including psychological, emotional, and sexual abuse; disconnection from his language and culture; and the loss of his family and community. Told as remembrances infused with insights gained through his long healing process, Fontaine goes beyond the details of the abuse that he suffered to relate a unique understanding of why most residential school survivors have post-traumatic stress disorders and why succeeding generations of Indigenous children suffer from this dark chapter in history. With a new foreword by Andrew Woolford, professor of sociology and criminology at the University of Manitoba, this commemorative edition will continue to serve as a powerful testament to survival, self-discovery, and healing. |

|

Like thousands of Aboriginal children in Canada, and elsewhere in the colonized world, Xatsu'll chief Bev Sellars spent part of her childhood as a student in a church-run residential school. These institutions endeavored to "civilize" Native children through Christian teachings; forced separation from family, language, and culture; and strict discipline. Perhaps the most symbolically potent strategy used to alienate residential school children was addressing them by assigned numbers only―not by the names with which they knew and understood themselves. In this frank and poignant memoir of her years at St. Joseph's Mission, Sellars breaks her silence about the residential school's lasting effects on her and her family―from substance abuse to suicide attempts―and eloquently articulates her own path to healing. Number One comes at a time of recognition―by governments and society at large―that only through knowing the truth about these past injustices can we begin to redress them. |

|

A young girl notices things about her grandmother that make her curious. Why does her grandmother have long, braided hair and beautifully coloured clothing? Why does she speak Cree and spend so much time with her family? As the girl asks questions, her grandmother shares her experiences in a residential school, when all of these things were taken away. |

| The Marrow Thieves Just when you think you have nothing left to lose, they come for your dreams. Humanity has nearly destroyed its world through global warming, but now an even greater evil lurks. The indigenous people of North America are being hunted and harvested for their bone marrow, which carries the key to recovering something the rest of the population has lost: the ability to dream. In this dark world, Frenchie and his companions struggle to survive as they make their way up north to the old lands. For now, survival means staying hidden - but what they don't know is that one of them holds the secret to defeating the marrow thieves. |

| Phyllis’s Orange Shirt The true story of Phyllis Webstad and her orange shirt that started the "Orange Shirt Day - Every Child Matters" movement. The true story of Phyllis Webstad and her orange shirt that started the "Orange Shirt Day - Every Child Matters" movement. When Phyllis Webstad (nee Jack) turned six, she went to Residential School for the first time. On her first day at school, she wore a shiny orange shirt that her Granny had bought for her, but when she got to the school, it was taken away from her and never returned. This is the true story of Phyllis and her orange shirt. It is also the true story of Orange Shirt Day (an important day of remembrance for First Nations and non-First Nations peoples). |

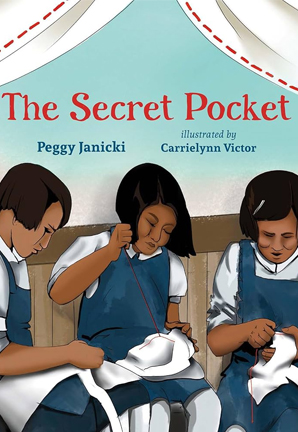

| The Secret Pocket The true story of how Indigenous girls at a residential school sewed secret pockets into their dresses to hide food and survive. Mary was four years old when she was first taken away to the Lejac Indian Residential School. It was far away from her home and family. Always hungry and cold, there was little comfort for young Mary. Speaking Dakelh was forbidden and the nuns and priest were always watching, ready to punish. Mary and the other girls had a genius idea: drawing on the knowledge from their mothers, aunts and grandmothers who were all master sewers, the girls would sew hidden pockets in their clothes to hide food. They secretly gathered materials and sewed at nighttime, then used their pockets to hide apples, carrots and pieces of bread to share with the younger girls. Based on the author's mother's experience at residential school, The Secret Pocket is a story of survival and resilience in the face of genocide and cruelty. But it's also a celebration of quiet resistance to the injustice of residential schools and how the sewing skills passed down through generations of Indigenous women gave these girls a future, stitch by stitch. |